McLaren Park, the big park of the southeast corner of San Francisco in which I walk almost every day, is is kept in a state of loose order. Trails are cleared, fallen trees cut and new ones planted, and playing fields mowed. Poison oak allowed to grow? Nope. Most everything else that makes itself comfortable there? Yes. It is home to redwood groves and eucalyptus forests, open meadows and scrublands. Tucked into its center is an old green house (green house, not greenhouse) where the maintenance team keeps their offices and a large, fenced vegetable and fruit garden. Most of the fruit in McLaren Park, however, is outside of that fence. The park is full of blackberries.

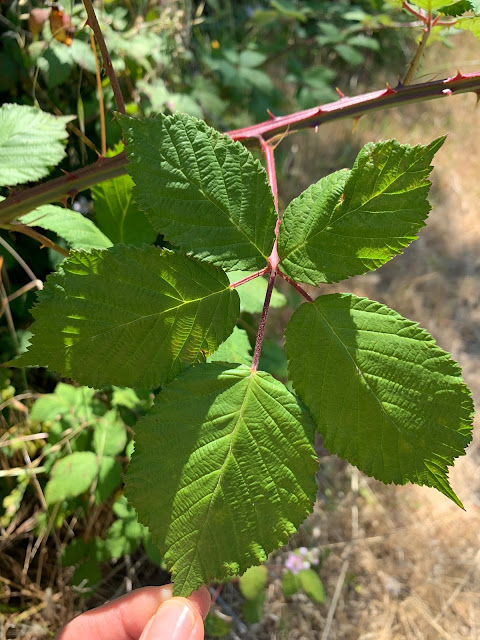

Blackberries are in the rose family, clearly evident in their thorns, caning habit, leaf structure, and flowers. Two species of blackberry compete for superiority in McLaren.

This is a Himalayan blackberry, Rubus bifrons. It is a vigorous invasive plant that can take over whole hillsides if there is even a little water available. Himalayan blackberries have five (sometimes seven) leaves on each stem, arching canes with large recurved thorns, and relatively large white flowers.

Most of the berry thickets south of Mansell, the biggest road that splits the park, are Himalayan blackberries; there are also other large thickets on the park's eastern edges, and of course, near the "lakes" and the spring.

This is California blackberry, Rubus ursinus. It has three leaves instead of five on each stem, slender thorns that stick straight out of the canes, smallish white flowers, and the whole plant grows a little lower to the ground than the Himalayan blackberry. While the plants will grow with little water, they won't produce much fruit without access.

Most of the California blackberry I have found in the park is north of Mansell, near the two "lakes" or fed by spring water. In the park, I have only seen it growing in partial sun.

Both Himalayan blackberry and California blackberry produce very tasty fruit and every August and September, I fill containers of fruit to munch on and cook with.

But, they're not the only two varieties of Rubus in the park. There are others that are causing me a lot of delight as I try to figure out what they are.

Consider this, which looks to my eye, like a boysenberry, a hybrid of a bunch of different Rubus, including Rubus ursinus. Is it? Or, is it a different hybrid that emerged from the crossing of ursinus and bifrons? Or a crossing of one of the two and the maintenance team's berry bushes from behind the fence? A fence won't stop a bee. I have only seen one patch of this type, growing in a willow thicket fed by the spring. Its leaves are big and floppy, its fruit over an inch long, and its thorns slender.

And what about this one? It has smooth leaves, usually three per stem, completely thornless canes, and bright pink flowers. I've found several large thickets of them on either side of the meadow near Gambier Plaza. Could it be some kind of cross with a Rubus canadensis, a thornless berry? How would that cross even happen? And, where did that pretty pink flower come from?

In some cases, a couple varieties grow all tangled up together, like this.

I'm sure there are those who would like all the berry bushes gone in McLaren, replaced by well-tended flower beds or more pickleball courts, both of which are good, important things. But so is all this undefined wildness. Something inside me has to observe and and seek out plant patterns, then question and research. These Rubus thorns (or lack thereof) scratch me in ways I need.

Thank you, maintenance team in the old green house. You keep the park just right.

Comments